An SRE's Guide to Linux Boot Processes

Table of Contents

A walkthrough of Linux Boot from an Ubuntu perspective to understand what goes on behind the hood.

One of the fundamentals for a modern SRE to know is Linux boot. Not only for debugging startup issues or optimising boot time, but also to develop an understanding of the base layers of Linux and how they communicate with each other.

This guide goes through the boot process, explains PID 1 (systemd) and essential early services. For simplicity, this is explained from an Ubuntu perspective. The article ends with some tools to explore the concepts discussed.

Note: A significant portion of the processes discussed here won’t be available on a typical minimal Ubuntu image used by your containerised applications and web servers, but are mostly targeted towards VMs, bare metal, etc.

Boot Sequence at a Glance #

The order of the boot sequence is as follows:

Firmware (UEFI/BIOS)

↓

Bootloader (GRUB2)

↓

Kernel (vmlinuz + initramfs)

↓

PID 1 (systemd)

↓

System targets & services

Kicked off immediately after power is supplied, UEFI is the intermediary between hardware and OS. UEFI is a superior version of BIOS with quicker boot times, more memory to support larger drivers, Secure Boot, mouse support and more. The UEFI specification defines a boot manager that first checks boot configuration and then executes the OS bootloader.

Boot configuration information, including system paths, is stored in NVRAM and references files in the EFI System Partition. For Ubuntu, the shim bootloader (developed by Red Hat and signed by Microsoft for Secure Boot) is used as the first-stage EFI application.

Ubuntu uses GRUB 2 (AKA grub-efi-amd64-signed) as the second-stage bootloader. This is installed with the OS and has a simple command-line interface that executes commands like e, c or other GRUB-specific commands. GRUB is responsible for loading the selected kernel into memory (vmlinuz and initramfs in Ubuntu case) and handing over boot control to the kernel. Alternatively, boot control can be passed to another bootloader (AKA chain loading).

From here onwards, the kernel stage will complete hardware initialisation and hand over control to PID 1, which will initialise system targets and services.

The Kernel Wakes Up #

vmlinuz is the compressed kernel image that GRUB loads into memory and executes. It is a statically linked executable file containing the Linux kernel, located at /boot/vmlinuz-<VERSION>. As soon as it takes over control, it first initialises CPU and memory management. Some of these can be tuned from /proc. Next, hardware detection and initialisation takes place. This is achieved via initramfs, which provides the needed drivers.

initramfs is a compressed archive containing a temporary root filesystem that helps mount the real root filesystem. This solves a chicken-and-egg problem: the drivers required for mounting the root filesystem may be located on that same filesystem. It lives at /boot/initrd.img-<VERSION>. The process is as follows:

- Kernel unpacks

initramfsas a temporary root at/ - Kernel then runs the

/initscript frominitramfs. This loads:- Essential kernel modules like disk and filesystem drivers, LVM, RAID, disk decryption (if required)

- Userspace tools like

busybox, mount utilities udevrules for device discovery- Scripts that find and mount the root filesystem

- Then, the actual root filesystem gets mounted at

/root switch_rootpivots to the real root and executes/sbin/init(init program)

vmlinuz also sets up interrupt handlers like timer interrupts, inter-processor interrupts, hardware IRQs, machine check exceptions, etc. These are not often interacted with, but a high number of interrupts could point to a hardware problem during boot. This can be inspected at /proc/interrupts. Another major role of the kernel is to spawn the first kernel threads. Some notable ones:

kthreadd(PID 2): Parent kernel thread that spawns workersksoftirqd: Handles soft interrupts—deferred work from hardware interrupt handlers (e.g., network packet processing, disk I/O completion). Only used when softirqs accumulate, to avoid starving userspace processes.kworker: Performs deferred kernel tasks from the work queue systemrcu_sched/rcu_preempt: Manages RCU (Read-Copy-Update) synchronisation by setting grace periods for safe data removalmigration: Moves processes between CPU cores for load balancingkcompactd: Handles memory compaction to overcome external memory fragmentationkswapd: A term that DBAs would be familiar with 😏. It is responsible for swapping unused, dirty pages from RAM to disk. Helps with memory reclaim.

PID 1 Takes Over #

PID 1 is the first userspace process. On Ubuntu, this is systemd. It runs until the system shuts down. There is a long history of init systems, including SysVinit, OpenRC, and Upstart (which Ubuntu used until 15.04). Let’s focus without taking a side in this holy war and list some important points. systemd handles dependencies (and their dependencies) through unit files. A unit is a resource that systemd manages. The configuration files are also called unit files.

/lib/systemd/system hosts the unit files installed by packages. For local modifications, use the /etc/systemd/system directory. A unit can be many things: a service, network resource, device, filesystem mount, or resource pool. To override unit file settings, create a directory named after the unit file with a .d suffix and add .conf files to change attributes. Some unit file features:

- Socket-based activation: Activate a service when a connection arrives on a particular socket.

- Bus-based activation: Delay service activation until a D-Bus interface is published.

- Device-based activation: Start the service when associated hardware becomes available (based on

udevevents). - Implicit dependency mapping:

systemdbuilds an implicit dependency tree, but dependencies can be set explicitly too. - Security hardening: Limit filesystem access, kernel capabilities, network access, etc.

Common types of units:

.service: Run a daemon or application.socket: Manage a network socket, IPC socket, or FIFO buffer.device: Represent audev/sysfs-detectable device.mount: Manage mount points (some auto-generated from/etc/fstab;.automountunits require a matching.mountunit).swap: Manage swap space activation.target: Synchronisation points for grouping units and representing system states (e.g.,multi-user.target,graphical.target).path: Monitor filesystem paths usinginotifyand trigger associated services.timer: Schedule services based on cron-like patterns.slice: Manage resources using cgroups for CPU, disk I/O, and memory limits. More on control groups

Historically, SysVinit defined runlevels from 0 to 6 to represent system states. systemd manages this using system targets:

poweroff.target: Shuts down the system. (Runlevel 0)rescue.target: Single-user mode—for admin and recovery. (Runlevel 1)multi-user.target: Multi-user mode with networking—default for servers. (Runlevel 2, 3, and 4)graphical.target: Multi-user mode with GUI and network—default for desktops. (Runlevel 5)reboot.target: Reboots the system. (Runlevel 6)

Ubuntu uses graphical.target or multi-user.target based on the installation type.

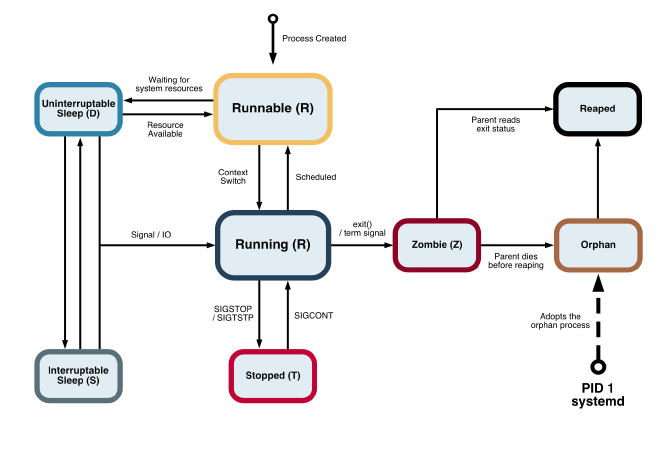

Another responsibility of systemd is reaping zombie processes and adopting orphans. These are distinct: a zombie is a terminated process whose parent hasn’t yet read its exit status; an orphan is a running process whose parent has terminated. To understand this, we need to briefly look at Linux process states.

When a child process terminates, it becomes a zombie until its parent calls wait() to read the exit status. The kernel notifies the parent via the SIGCHLD signal. If the parent terminates before calling wait(), the orphaned zombie is adopted by PID 1 (systemd), which reaps it.

Essential Early Services #

Before listing some essential services that run on Ubuntu, here’s a sample dependency chain. Most key services we run in production require one or more of these:

basic.targetnetwork-pre.targetnetwork.target(networkdorNetworkManager)network-online.targetpostgresql.service,ssh.service

systemd-journald and rsyslog are two essential logging services that are often used together. The former can be queried via journalctl. It is a lower-level service with only socket dependencies and starts early in the boot process. rsyslog is a logging/log-forwarding service that writes to /var/log/*. It is ordered after network.target.

To create device nodes in /dev, systemd-udevd is used. It runs rules for hardware setup and listens for kernel device events. It is also a low-level service with only socket dependencies.

Two common networking services are systemd-networkd and NetworkManager. On production servers, systemd-networkd is often chosen for its minimal overhead and predictable behaviour. It requires network-pre.target and systemd-sysusers.service.

Good old ssh.service (OpenSSH) starts when the network is available, configured at /etc/ssh/sshd_config, and requires network.target.

cron.service runs scheduled jobs from /etc/crontab, /etc/cron.d/*, and user crontabs. It’s a low-level service with a basic.target requirement.

As a sample database service, I’ve chosen postgresql.service. It requires network.target for establishing connections. Since storage can be hosted remotely or locally, it also requires local-fs.target and remote-fs.target. Lastly, it expects systemd-journald.service to be running so it can log any startup errors before the engine’s own logging takes over.

Practical Examples #

Lastly, I want to close off with some useful commands for debugging Linux systems. Spin up a VM and SSH in (even minikube ssh should be enough to run most of these commands).

Process inspection #

ps -ef --forest(or usepstreeif your image includespsmisc): Displays process hierarchyps aux: Processes and their CPU and memory consumptiontop: Processes and resource usage in more detail (htopmay not be available everywhere)

systemctl commands #

The main tool for interacting with systemd and services:

list-units --type=service: Show service units and their statuses (filter further with--state=running)status <SERVICE>: Service details like state, PID, tasks, cgroups, docs, logslist-dependencies <SERVICE>(or use--reverse <TARGET>to see which services depend on the target)get-default: Show default boot target:multi-user.targetorgraphical.targetcat <SERVICE>: Display unit file contents

Boot analysis #

systemd-analyze: Total boot time listed as kernel + userspacesystemd-analyze blame: Services sorted by startup time, slowest firstsystemd-analyze critical-chain: Shows the text-based dependency chain that determined boot timesystemd-analyze plot > boot_image.svg: Generates a visual SVG timeline of the boot process

graphical.target @852ms

└─multi-user.target @852ms

└─ssh.service @130ms +55ms

└─basic.target @124ms

└─sockets.target @124ms

└─podman.socket @124ms +808us

└─sysinit.target @122ms

└─local-fs.target @122ms

└─data.mount @132ms

└─local-fs-pre.target @122ms

└─systemd-tmpfiles-setup-dev.service @106ms +14ms

└─systemd-sysusers.service @99ms +6ms

└─systemd-remount-fs.service @92ms +5ms

└─systemd-journald.socket @80ms

└─-.mount @63ms

└─-.slice @63ms

journalctl -b: Show logs from current boot (use-b -1for previous boot)- Inspecting PID 1 via

/proc(systemdinformation):cat /proc/1/cmdline: Command line argumentscat /proc/1/status: Status report ofsystemd

Kernel threads #

cat /proc/softirqs: Softirq counts per CPUcat /proc/interrupts: Hardware interrupts per CPU and devicempstat -I ALL 1: Interrupt statistics (requiressysstat)

initramfs inspection #

lsinitramfs /boot/initrd.img-$(uname -r): List contentsunmkinitramfs /boot/initrd.img-$(uname -r) /tmp/initramfs: Extractinitramfsfor inspection

Logs and debugging #

journalctl -u <SERVICE> -b: Logs for a service from current bootjournalctl -p err -b: Error-level messages from current bootdmesg -T: Kernel ring buffer messages (for early boot and hardware problems)